African American Spirituals and Black Lives Matter:

How to prepare for the Second Civil Rights Movement

History Lesson

Summary

What were the songs that endured from times of slavery into the Civil Rights movement?

How is it that “coded” African American spirituals, made to alleviate pain and suffering, and to secretly inform enslaved people that it was time to flee or revolt, have survived for centuries?

How have these songs of strength evolved through the Civil Rights movement, finding relevance to the Black Lives Matter movement of today?

Songs are a part of Maryland’s rich oral, written, and musical history. Songs, like flowers, are constantly changing, and have many different names.

The Maryland Spirituals Initiative is about the essential role of spirituals as America’s finest art form.

Noted by W.E.B. DuBois in 1903 as music that “stirred him strangely,” spirituals or “sorrow songs,” as he called them, were becoming regarded by an international audience as the most important music in America.

James Weldon Johnson regarded spirituals as America’s only folk music.

Why are Ruth Starr Rose’s 100-year old depictions of African American spirituals relevant today?

They reflect the religious beliefs of Maryland’s founding black families.

Beginning in the 1920’s, Rose created the largest representation of African American spirituals prior to the Civil Rights Movement. The Sunday Star, Washington, D.C., April 29 (Sunday), 1956, “Interpretation of Spirituals,” quoting James A. Porter, “probably the most sympathetic visual interpretation of the Negro spirituals yet to appear in the United States.” Her show was extended due to popularity. The invitation to opening by Howard University’s Agnes DeLano lists her bio, adding, “Struck by a certain joy in their [African American] labor which she attributes to their deep spiritual sense, Rose was determined to do a visual series of Negro spirituals.”

Father of African American art history, Howard University’s James A. Porter wrote in the catalogue about her spirituals, “This interesting series of prints is the most comprehensive, and probably the most sympathetic visual interpretation of the Negro Spirituals yet to appear in the United States. Although the Negro Spirituals have been interpreted by numerous artists in many different media of the visual arts, no single artist has approached the extensive treatment accorded by Mrs. Rose to this them.” Her work is relevant as much as it was during the nascent Civil Rights movement as it is in 2020 as we experience BLM, also known as the second Civil Rights movement.

Ruth Starr Rose worked with the congregation to envision spirituals.

As we experience the second Civil Rights Movement today, her work remains relevant.

Here are three spirituals that sum it all up:

SONG #1: KEEP YOUR HAND ON THE PLOW

SONG #2: PHARAOH'S ARMY GOT DROWNDED

SONG #3: HE'S GOT THE WHOLE WORLD IN HIS HANDS

Song #1: The title, Keep your hand on the plow, is also known as Keep your eyes on the prize and Mary wore three links of chain.

Summary of Song #1

In both of the artist’s lithographic and serigraphic versions, a black and a white farmer walk together side by side, guiding a plow pulled by two mules. Beneath their feet, angels work at the forge of Vulcan, the Roman god of fire to convert weapons into farm equipment. Behind the farmers, menacing demon sits astride a missile, swooping down on the farmers in an attempt to destroy them. With a focus on their plow and mule team, the farmers ignore the devil, pointing upwards to the radiating rays of light emanating from above. They work together to plant crops to feed their people.

The swirling, circular composition encompasses the sun-filled heavens, and depicts a decidedly positive outlook on the future of race relations. Rose positioned the scene atop a flattened map of the United States, situating it firmly within the context of America’s struggle for civil rights.

The spiritual evolved and was important in the Civil Rights movement.

A black and a white farmer work together to plant crops to feed their people.

The swirling composition encompasses the heavens, depicting hope for the future of race relations.

The flattened map of the U.S. symbolizes America’s struggle for civil rights.

A menacing demon swoops down on the farmers. Vulcan converts his weapons into farming tools.

Mahalia Jackson, Bob Dylan, and Pete Seeger adapted this song in their cry for freedom.

Song #2: Pharaoh’s army got drownded

This song of liberation has variations:

Let my people go

Go down, Moses

Didn’t old pharaoh get lost

Oh sister Mary, don’t you weep

Summary of Song #2

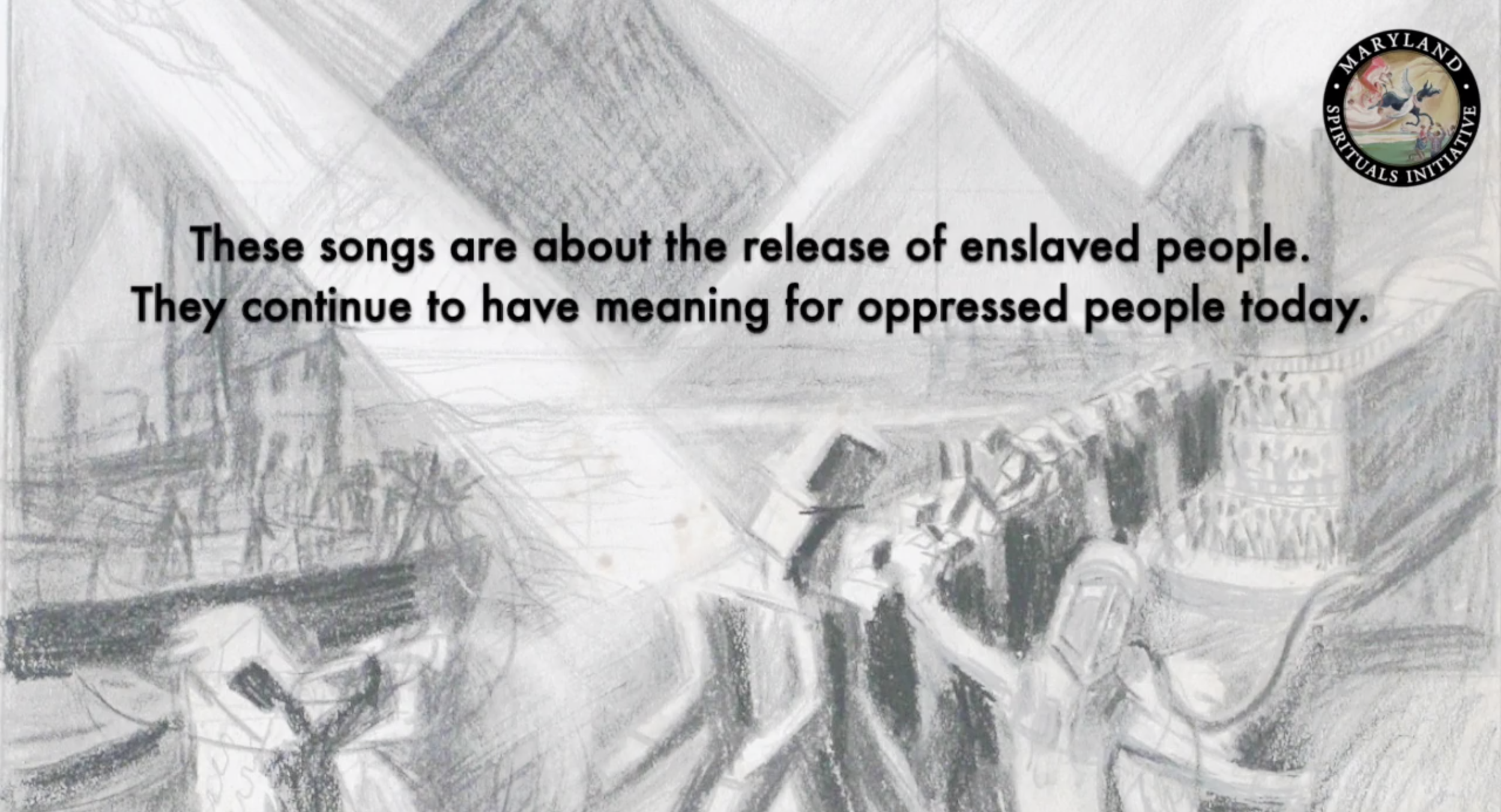

Being a basic theme of the release of an oppressed people from bondage these songs have meaning not only for other days, but look to more freedom now for the colored citizens.

One day in Maryland I was visited by the preacher of the African Methodist church and asked if I would do a painting for the altar–and how much I would charge. Telling him I would be glad to do the painting just for the pleasure of having his people enjoy it, I used this design of “Pharaoh’s army got drownded,” It was done on a large plaster panel in the ancient technique of true fresco.

After completion, it was moved two miles down the long lane, and through the dark southern pine forests to the little church of Copperville, Maryland. With the help of the elders and the preachers, the painting had a safe though adventurous journey through the mud, on the running board of the preacher’s car. Installed at last in its place of honor above the pulpit and the Bible, it was unveiled with much ceremony, with singing and with ringing words of preaching, ennobled by the fine native dignity of the Negroes.

In gratitude, the brethren of the church asked me if they could come to my house in June, when the honey locust is blooming by the tidewater and bring a chorus of fifty singers. The great day came; turning into a festival of white and colored for the benefit of the Copperville church. Choruses and quartets sang, and a young Negro preacher spoke, “Lo, how good and how beautiful it is for brethren to dwell together in unity.”

“The preacher of the African Methodist church asked if I would do a painting for the altar. After completion, it was moved to the church at Copperville, Maryland.” –Ruth Starr Rose

These songs are about the release of enslaved people. They continue to have meaning for oppressed people today.

Years later Rose reinterpreted Let my people go. In the print, Rose included people of African, Hispanic, and First Nation descent. Also the incarcerated (left) and women (right).

“This is the first work of art created by a white person for a black church.” –The Christian Science Monitor, 1955

Song #3: He’s got the whole world in his hands

Summary of Song #3

Ruth Starr Rose made a black and white lithograph as well as a color silkscreen print in the early 1950’s, and here are her words describing design and intent:

Also known as “Right in the palm of God's Hand,” this anonymous African American spiritual has its origins in the Book of Job (12:10), with the passage, “In His hand is the life of every living thing and the breath of every human being.” The song celebrates a world in which, under God’s care, everyone is treated with compassion and respect.

In the black and white print, the hands of God hold and protect an African American worker, while the humble animals worship the wonder as they watch below. The silkscreen of the same subject, Right in the Palm of God’s Hand is done in full rich color. This print shows again the hands of God, holding a worker but not a man of any particular race, not necessarily a Negro worker. I want my prints to stand as an expression of universal brotherhood. It portrays the power and presence of God in storm and stress, protection his people on earth.

“This song celebrates a world under God’s care. Everyone is treated with compassion and respect. The hands of God protect an African American worker. The humble animals worship the wonder from below.” –Ruth Starr Rose

“The hands of God hold a worker, not a man of any particular race, not necessarily a Negro worker. I want my prints to stand as an expression of universal brotherhood.” –Ruth Starr Rose

Speech therapist Kenay Sudler and educator/songwriter/singer Kentavius Jones enjoy remote learning with Tilghman Paca Logan.

Case Study: Black Lives Matter in Maryland. Standing up for Dr. Andrea Kane.

Credits and a big Thank you!

Nina Simone, I wish I knew how it would feel to be free; Vondie Curtis-Hall, Hold on [Harriet Tubman, 2019]; Pete Seeger, Keep your eyes on the prize; Paul Robeson, Go down Moses; Cynthia Erivo, Let my people go [Harriet Tubman, 2019]; Nina Simone, He’s got the whole world in his hands; Kentavius Jones with Shay Springer and Chris Dorr, He’s got the whole world in his hands.